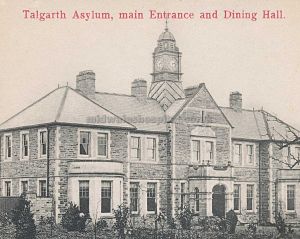

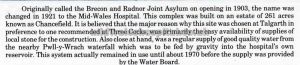

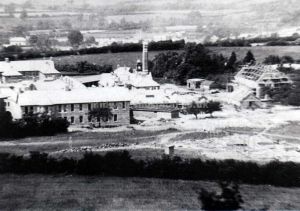

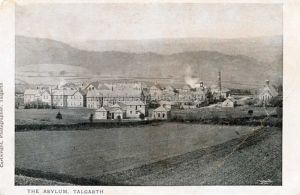

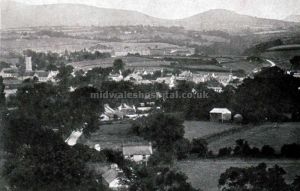

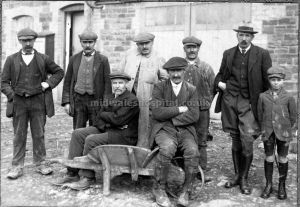

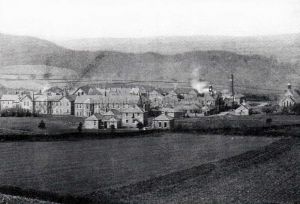

Older Images Of The Former Asylum

Eugenics

The study of factors that influence the hereditary qualities of future generations. It may be thought of as both a science and a social movement. Eugenics proposes to improve humanity’s future by increasing the number of children produced by persons who are, by some definition, superior and by reducing the number produced by persons who are physically or mentally deficient. Attempts to encourage larger families from superior parents are called positive eugenics, attempts to reduce the number of children from defective parents negative eugenics.

The nineteenth century asylum was as much a prison as a house of cure. In the early years of that century there was hope of improvement but by its end, and especially after Darwin’s Origin of Species had appeared, the prevailing opinion was that madness was hereditary and that the possessed should be removed from our midst and locked permanently up.

Initially doctors hunted for a cause, dissected brains, pulled out nerves, examined the blood, measured spinal columns, weighed glands, scraped, scratched and stumbled. Mental disease could be nothing more than an infection. Find it. Burn it down. Their patients languished. Their patients screamed. Their patients aged and greyed and failed. The rest of the world refused to look.

In 1858, two sentences captures the essence of the day. ‘Insanity is purely a disease of the brain. The physician is now the responsible guardian of the lunatic and must ever remain so.’

By the turn of the 20th century, psychiatry was still relatively new. The term ‘psychiatry’ emerged in Britain only in 1858. Prior to that there were only ‘mad-doctors’ or ‘alienists’ and many of the large new asylums were run by ‘lay’ (i.e. non-medical) administrators.

In the Victorian period, fledgling psychiatry was faced with two challenges. One was to wrest political control of the asylum system from lay administrators. Another was to construct a credible knowledge base to underpin a form of medical authority over lunacy.

For over fifty years this position remained in the ascendancy in debates about lunacy. Indeed, the asylum system was taken over successfully by medical superintendents and contributed to the eugenic thought in Western intellectual culture.

However, this self-confidence was soon undermined by the ‘shellshock problem’ emerging after 1914. There was a fundamental incompatibility between a eugenic view about lunacy, the legacy from Victorian asylum doctors, and the grim reality of officers and gentleman and working class volunteers (‘England’s finest blood’) breaking down with predictable regularity in the trenches of the ‘Great War’.

To offer a eugenic explanation for the newly and, at first, confusingly, described neurotic reactions, witnessed in these traumatised soldiers, was tantamount to treason. Not only was the monopoly of this analysis now broken, but other modes of psychiatric thinking were made possible.

Neurosis, not just psychosis, now came within the ambit of psychiatry and psychoanalysis was finally offered some legitimacy after its pre-War dismissal by the leaders of psychiatry and neurology.

A year after the end of the War both the British Psychoanalytical Society and the Medical Section of the British Psychological Society were established. This moment could be read as the beginnings of a long heavyweight contest between biological psychiatrists and medical psychotherapists.

The poet Sassoon described this strange process in the following way:

“Shell-shock. How many a brief bombardment had its long-delayed after-effect in the minds of these survivors, many of whom had looked at their companions and laughed while the inferno did its best to destroy them. Not then was their evil hour, but now; now, in the sweating, suffocation of nightmare, in paralysis of limbs, in the stammering of dislocated speech. Worst of all, in the disintegration of those qualities through which they had been so gallant and selfless and uncomplaining – this, in the finer types of men, was the unspeakable tragedy of shell shock” (Siegfried Sassoon Sherston’s Progress)