The York Retreat developed from the English Quaker community both as a reaction against the harsh, inhumane treatment common to other asylums of that era, and as a model of Quaker therapeutic beliefs. A common belief at the time was that the mad were wild beasts. The recommended medical practices included debilitating purges, painful blistering, long-term immobilization by manacles, and sudden immersion in cold baths – all administered in regimes of fear, terror and brutality. But the Quakers maintained that the humanity and inner light of a person could never be extinguished. A specific trigger was the death in 1790 of a Quaker, Hannah Mills, a few weeks after she had been admitted to the York Asylum (now known as Bootham Park Hospital). The asylum had not let her friends or family visit her, and they became suspicious. Visiting afterwards to investigate the conditions, the Quakers found that the patients were treated worse than animals.

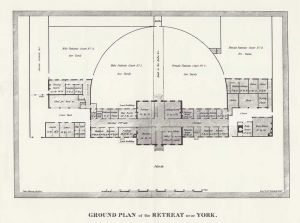

The Quaker William Tuke was enlisted and took charge of a project to develop a new form of asylum. He appealed to Quakers, personal acquaintances and physicians for funds. He spent two years in discussion with, and issuing explanatory statements to, the local Quaker group (York Monthly Meeting), working out the fundamental principles of the proposed institution. Tuke and his personal physician, Timothy Maud, educated themselves about the current views on “madness” and its treatment. Tuke’s conviction, however, was in the importance of benevolence and a comfortable living environment encouraging reflection. Tuke also worked with architect John Bevans to design the new building.

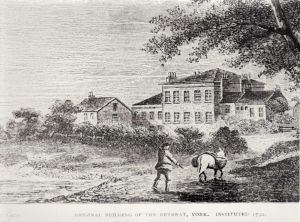

The Retreat opened in 1796 in the countryside outside York. It was planned to take in about 30 people but started with just three, then eight. Unlike mental institutions of the time, there were no chains or manacles, and physical punishment was banned. Treatment was based on personalized attention and benevolence, restoring the self-esteem and self-control of residents. An early example of occupational therapy was introduced, including walks and farm labouring in pleasant and quiet surroundings. There was a social environment where residents were seen as part of a large family-like unit, built on kindness, moderation, order and trust. There was a religious dimension, including prayer. Inmates were accepted as potentially rational beings who could recover proper social conduct through self-restraint and moral strength. They were permitted to wear their own clothing, and encouraged to engage in handicrafts, to write, and to read books. They were allowed to wander freely around The Retreat’s courtyards and gardens, which were stocked with various small domestic animals.

There was some minimized use of restraint. Door locks were encased in leather, the bars on windows made to look like window frames, and the extensive gardens included a sunken wall that was impassable yet barely visible. Straitjackets were sometimes used, at least initially, as a threat or a last resort There was little formal medical involvement and an apothecary, Thomas Fowler, served as physician. He gave the standard medical treatments “ample trial” but reluctantly and “courageously” abandoned them as failures. Fowler worked with George Jepson, the first superintendent of the retreat, and the two gradually concluded that the use of usual fear tactics actually made patients worse, and allaying patient’s fears helped them. Jepson was said to have been authoritative yet patient, attentive, observant, kind, and open to new ideas due to limited formal medical training. He arrived at the same time as a talented Quaker nurse Katherine Allen, and the two married in 1806, thus heading the Retreat together.

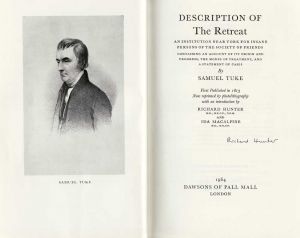

The approach of The Retreat was widely derided at first. William Tuke noted that “All men seem to desert me.” However, it became a model around the world for more humane and psychologically-based approaches. The work was taken on by other Quakers, including Tuke’s son Henry Tuke who co-founded the retreat, and Samuel Tuke who helped popularize the approach and convince physicians to adopt it in his 1813 book Description of the Retreat near York. In doing so, Samuel Tuke popularized his use of the term moral treatment that he had borrowed from the French “traitement moral” being used to describe the work of Pussin and Pinel in France (and in the original French referring to morale in the sense of the emotions and self-esteem, rather than rights and wrongs). The term came to refer to a number of moves towards more humane approaches that occurred toward the end of the 18th century in the context of Enlightenment thinking, including also the work of Chiarugi in Italy. Ideas of “moral” management were incorporated, and used for various therapeutic and custodial purposes, in asylums and therapeutic communities around the world.

In 1847 the first formal “medical” superintendent was appointed. Moral therapy was gradually replaced by medication, special diets and hydrotherapy. The size of the institution grew and the formerly close-knit community ethos was left behind. In addition, both Quaker influence and the number of Quaker patients decreased through the century. After the initial period for which it is best known, therefore, there were marked changes in management, therapy and client groups.

Between 1880 and 1884, most patients of The Retreat were under 50, single, and non-Quaker. A majority have been assessed today as having met criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a mood disorder. The majority experienced delusions, with the most common being of persecution, grandeur and guilt, whilst about a third had religious content. Just under a third of patients were suicidal. Drug therapy was commonly prescribed. Just over a third of patients had a history of assault on other patients or asylum staff. About a tenth of patients were force-fed at some stage during their stay. About a half of patients were discharged within a year of admission, with the prognosis being better for patients with a mood disorder than for schizophrenia, but just under a third remained in the asylum for five or more years.